Artist Statements

Monkey Wrench

Pat Dougherty

oil and acrylic

The Journey by Mary Oliver

One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,

though the voices around you

kept shouting

their bad advice --

though the whole house

began to tremble

and you felt the old tug

at your ankles.

"Mend my life!"

each voice cried.

But you didn't stop.

You knew what you had to do,

though the wind pried

with its stiff fingers

at the very foundations,

though their melancholy

was terrible.

It was already late

enough, and a wild night,

and the road full of fallen

branches and stones.

But little by little,

as you left their voice behind,

the stars began to burn

through the sheets of clouds,

and there was a new voice

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do --

determined to save

the only life that you could save.

Pat Dougherty

oil and acrylic

The Journey by Mary Oliver

One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,

though the voices around you

kept shouting

their bad advice --

though the whole house

began to tremble

and you felt the old tug

at your ankles.

"Mend my life!"

each voice cried.

But you didn't stop.

You knew what you had to do,

though the wind pried

with its stiff fingers

at the very foundations,

though their melancholy

was terrible.

It was already late

enough, and a wild night,

and the road full of fallen

branches and stones.

But little by little,

as you left their voice behind,

the stars began to burn

through the sheets of clouds,

and there was a new voice

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do --

determined to save

the only life that you could save.

Blue-Triadic Churn Dash

Linda Black

fabric

My idea when designing this quilt was to work with transparency. To show that many small pieces can make another larger piece within them. Hidden in plain sight.

At first glance we see the large image, then realize that all the parts of it are made by combining the parts of smaller images, simply by changing the “value”, or lightness/darkness of those pieces. In the same way, the message behind the quilt pattern was hidden in plain sight. So that only those who had the key could read the message.

I feel it also speaks to the way that many individuals, of varying lightness and darkness, came together to carry out a greater purpose – Freedom.

Linda Black

fabric

My idea when designing this quilt was to work with transparency. To show that many small pieces can make another larger piece within them. Hidden in plain sight.

At first glance we see the large image, then realize that all the parts of it are made by combining the parts of smaller images, simply by changing the “value”, or lightness/darkness of those pieces. In the same way, the message behind the quilt pattern was hidden in plain sight. So that only those who had the key could read the message.

I feel it also speaks to the way that many individuals, of varying lightness and darkness, came together to carry out a greater purpose – Freedom.

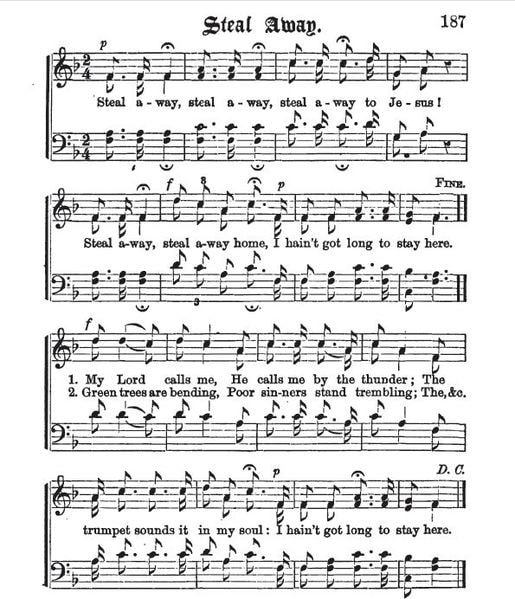

Wagon Wheel – It’s Time

Janet Chalker

mosaic (glass, tile and watch pieces)

In every journey there is a moment when you have to commit. You must make a plan, pack up and decide it is time to leave; decide it’s time to change. This quilt block, for me, represents that moment. It is layered with spiritual connections – the Carpenter’s Wheel, referencing Jesus the carpenter and Ezekiel’s wheel which ran on faith and grace. We are told to “steal away to Jesus”, to find our own freedom, our own path.

Janet Chalker

mosaic (glass, tile and watch pieces)

In every journey there is a moment when you have to commit. You must make a plan, pack up and decide it is time to leave; decide it’s time to change. This quilt block, for me, represents that moment. It is layered with spiritual connections – the Carpenter’s Wheel, referencing Jesus the carpenter and Ezekiel’s wheel which ran on faith and grace. We are told to “steal away to Jesus”, to find our own freedom, our own path.

Bear Paw

Desmond Black

wood

This challenge intrigued me in all the messaging and the risks all participants undertook, both in escaping but also assisting those people in their flight. I took the challenge within my artistic domain, which is woodworking, and chose the Bears Paw block, since the message was to “follow the bears tracks through the woods to the cross roads”.

However, as I addressed the technical challenges of using wood as the medium I reflected on the messaging and how subtle, but in your face, it was done. Imagining a Bears Paw quilt openly airing on the front porch of a property for all to see, but only the knowledgeable able to “read” the meaning.

I decided to also place a subtle message within the 4 larger block pieces, recognizing not only the people in flight but also the helping hands that supported them through the journey.

Can you see the message?

Desmond Black

wood

This challenge intrigued me in all the messaging and the risks all participants undertook, both in escaping but also assisting those people in their flight. I took the challenge within my artistic domain, which is woodworking, and chose the Bears Paw block, since the message was to “follow the bears tracks through the woods to the cross roads”.

However, as I addressed the technical challenges of using wood as the medium I reflected on the messaging and how subtle, but in your face, it was done. Imagining a Bears Paw quilt openly airing on the front porch of a property for all to see, but only the knowledgeable able to “read” the meaning.

I decided to also place a subtle message within the 4 larger block pieces, recognizing not only the people in flight but also the helping hands that supported them through the journey.

Can you see the message?

|

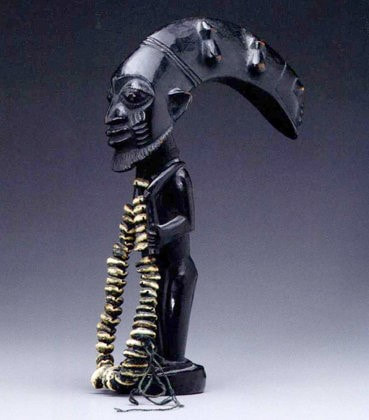

The Baptism of Eshu

Patrick Ellis mixed media assemblage Eshu, also spelled Eschu, also called Elegba, is a trickster god of the Yoruba of Nigeria, an essentially protective, benevolent spirit who serves Ifa, the chief god, as a messenger between heaven and earth. Eshu requires constant appeasement in order to carry out his assigned functions of conveying sacrifices and divining the future. My quilt pattern is crossroads. This pattern signified a very particular place in the journey north, but it was also a profoundly symbolic moment for enslaved people. While this crossroad might bring freedom, it was not a return or repatriation to a familial homeland, it was not a return to ancestral religions, nor was it necessarily a reuniting with family and kin. So much must be left behind in this crossing-over. Without homeland, family and kin, a community’s core memories, beliefs, rituals and cosmologies were often impossible to preserve. Many of these enslaved people would come to adopt the religion of the Europeans that were their allies in this journey to freedom. They were baptized into new memories, beliefs, rituals and cosmologies … but in this baptism, these converts would profoundly alter this European religion forever. I like to think that in the baptism of Eshu, the Gods of the Christianity found a vital partner in the work of redemption. I like to think that the trickster god of the Yoruba of Nigeria is still doing his work to connect heaven and earth. |

At a Crossroad – Moving Between Past, Present, Peace, and Power

Shelley Koopmann

oil

The quilt patten I chose is "Crossroads". For me, every minute of every day consists of numerous decisions, or crossroads, that affect one's life, just as it did back in the days of the Underground Railroad. The pattern of the woman hanging on the wall is from Bisa Butler's beautiful quilt. The crossroad pattern is behind her. The figure looking at it is a combination of Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman elected to the US Congress (holding up a peace sign), and Angela Davis, who was associated with the Black Panthers, a militant group fighting for that same peace, but in a more radical way (holding up the fist). Just two women who took different paths (crossroads) to achieve peace in the 60's.

Shelley Koopmann

oil

The quilt patten I chose is "Crossroads". For me, every minute of every day consists of numerous decisions, or crossroads, that affect one's life, just as it did back in the days of the Underground Railroad. The pattern of the woman hanging on the wall is from Bisa Butler's beautiful quilt. The crossroad pattern is behind her. The figure looking at it is a combination of Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman elected to the US Congress (holding up a peace sign), and Angela Davis, who was associated with the Black Panthers, a militant group fighting for that same peace, but in a more radical way (holding up the fist). Just two women who took different paths (crossroads) to achieve peace in the 60's.

Log Cabin

Nancy Laurent

mixed media

RUN AWAY SLAVES

Following the North Star

RUN AWAY SLAVES

Men, Women & Children

Held with Shackles & Chains

RUN AWAY SLAVES

Chased with Men & Horses, Guns & Hounds

RUN AWAY SLAVES

Looking for the “Log Cabin”

Looking for Freedom

Nancy Laurent

mixed media

RUN AWAY SLAVES

Following the North Star

RUN AWAY SLAVES

Men, Women & Children

Held with Shackles & Chains

RUN AWAY SLAVES

Chased with Men & Horses, Guns & Hounds

RUN AWAY SLAVES

Looking for the “Log Cabin”

Looking for Freedom

Shoofly

Revelle Hamilton

mixed media

I chose to do Shoofly. Not a lot Is known about this symbol. It Is thought that Shoofly

may refer to an actual person who might have aided escaping slaves. In the book Hidden in Plain Sight- A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad it says,"

Shoofly told them to dress up in cotton and satin bow ties and go to the cathedral church, get married and exchange double wedding rings".

I used Images of slaves as "fabric" for my version of the quilt block, Interpreting it in paper and collage.

Revelle Hamilton

mixed media

I chose to do Shoofly. Not a lot Is known about this symbol. It Is thought that Shoofly

may refer to an actual person who might have aided escaping slaves. In the book Hidden in Plain Sight- A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad it says,"

Shoofly told them to dress up in cotton and satin bow ties and go to the cathedral church, get married and exchange double wedding rings".

I used Images of slaves as "fabric" for my version of the quilt block, Interpreting it in paper and collage.

Bow Ties

Dick Hendrix

wood

“Shoofly told them to dress up in cotton and satin bow ties…”

Once escaping slaves were able to make their way to a location where they could freely mingle with free people of color, they needed to discard the worn and ragged clothing they had been wearing on their long and dangerous trek northwards. The Bow Tie quilt block was their reminder to clean up and dress like everyone else to avoid capture and return to the south.

Many of the quilts that were used to convey signals along the Underground Railroad were primitive because the makers were forced to use whatever materials they had available. These items were not decorative but had utilitarian purposes in addition to their use as a signpost on the Railroad.

In my piece, I’ve tried to remain true to this ideal. The block consists of 36 triangles cut from red cedar and yellow poplar logs. The red cedar triangles came from logs that were deadfall on my property. The yellow poplar triangles were fashioned from a log that came from my wife’s uncle’s workshop. The block is framed in pine strips that came from century-old pine that I inherited from my father over 20 years ago.

Dick Hendrix

wood

“Shoofly told them to dress up in cotton and satin bow ties…”

Once escaping slaves were able to make their way to a location where they could freely mingle with free people of color, they needed to discard the worn and ragged clothing they had been wearing on their long and dangerous trek northwards. The Bow Tie quilt block was their reminder to clean up and dress like everyone else to avoid capture and return to the south.

Many of the quilts that were used to convey signals along the Underground Railroad were primitive because the makers were forced to use whatever materials they had available. These items were not decorative but had utilitarian purposes in addition to their use as a signpost on the Railroad.

In my piece, I’ve tried to remain true to this ideal. The block consists of 36 triangles cut from red cedar and yellow poplar logs. The red cedar triangles came from logs that were deadfall on my property. The yellow poplar triangles were fashioned from a log that came from my wife’s uncle’s workshop. The block is framed in pine strips that came from century-old pine that I inherited from my father over 20 years ago.

Double Wedding Rings

Caroline Renard

mixed media

First I read and re-read Hidden in Plain View and underlined many a sentence, phrase and bookmarked everything. As you know I selected the double wedding band as my chosen vehicle to interpret the secret story of the quilts of the underground railroad. Understanding that this particular image was not necessarily a part of the “code”.

However, because of my personal history it spoke to me in many ways and in many respects. I found correlations. The subject of abuse is never an easy one and unfortunately is universal.

The part that stood out most to me was the subject of the Middle Passage. It was the water that drew me in initially as I love sailing and did so for many years on the Chesapeake Bay. Even now at my age I just bought a little dinghy so I could putter around the lake behind my home.

But the flow of the water, like life is one of turbulence and calm. Fair weather and following seas are what sailors want most. A squall however can come without warning and strikes unmercifully to the least prepared, leaving much damage in its wake.

So it was with this history in my mind that I approached my art.

These poor unsuspecting people were imprisoned through no fault of their own into a hell hole of despair, laid together in the spoon position in this their Middle Passage — the second leg of their journey across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe and Africa.

The Middle Passage has its equivalent to me of what is perceived as my Midlife Crisis. It was at age 40 that I began my art teaching career, Little did I know that it would in turn be a journey of breaking free from a life of left brain isolation, perceived expectations of a suburban housewife, and gradually understanding that I had something to say with my art. This in turn enabled me to become stronger, to question my preconceived “station” in life and standup for myself. This did not happen all at once. It took years.

Like the slaves, I realized that my “master” would never change, that the roses that came to me at my school were once again only a temporary fix—a device to “hoover” me in once again so the cycle could start all over again. And it did.

“40 years A Slave” was also my story.

In my art, I incorporated several techniques of African art. The calabashes of “Strength”, “Defiance” and “Home” are made from lino blocks and originate in the Adinkra symbols of Ghana.

Metal work is an important component of African art as well. The baby spoon symbolizes the importance of raising your children well so that kindness is a part of their character. It also eludes to the “spoon” position that the Africans were forced into as they were stored on the slave ships. The gold patterns I took directly from the illustrations of Mud Cloth from our reference book.

The portrait is of myself completed in 1999 at Nimrod. I remember thinking of Vincent when I painted it using oil sticks. The subsequent tear is new. The cowry shells are an important part of African culture, used as money and a position of status in their clothing accoutrement.

The black chain and the four ships represent the journey of no return into the unknown. They are relevant to me as I made that journey as a child from England to America. The ships themselves are the pieces used in a game I played that traversed the island of Great Britain.

Joining the two canvases was a challenge to me. My main concern was to show despair into joy. I have truly found that. My device was through color and obviously the circles for the double wedding band. I on purpose did not focus so much on the wedding band as the strength of the composition but more as a background for life events.

Not being a fiber artist, I found the use of fabric to be challenging. Using the circle shapes as transitions from one canvas to another I whip stitched each and left them as pockets into which I inserted scrolls with words written on them. They are removable.

One of my all time favorite spirituals is “Swing Low Sweet Chariot”. I understand that Harriet Tubman used it to warn her charges. The eyes are mine. There are many messages there.

Bookmarking my Faith represents my travels and solo journeys I have taken across the globe since I set myself free. The lace is from Burano, Italy.

The tree with the cardinal and subsequent verse down below is from a recent card I received from my missionary friend, Mary Beth. She and her husband are with Water.org and frequently in Africa digging wells for the villages.

Writing for me is a large part of my creative process and I write many times on my art. I tried to make it legible but also felt it was alright to be childlike.

Lastly, the heart in the center is one that I made when I became the new me. Deformed, Devalued and Demeaned. No more.

Caroline Renard

mixed media

First I read and re-read Hidden in Plain View and underlined many a sentence, phrase and bookmarked everything. As you know I selected the double wedding band as my chosen vehicle to interpret the secret story of the quilts of the underground railroad. Understanding that this particular image was not necessarily a part of the “code”.

However, because of my personal history it spoke to me in many ways and in many respects. I found correlations. The subject of abuse is never an easy one and unfortunately is universal.

The part that stood out most to me was the subject of the Middle Passage. It was the water that drew me in initially as I love sailing and did so for many years on the Chesapeake Bay. Even now at my age I just bought a little dinghy so I could putter around the lake behind my home.

But the flow of the water, like life is one of turbulence and calm. Fair weather and following seas are what sailors want most. A squall however can come without warning and strikes unmercifully to the least prepared, leaving much damage in its wake.

So it was with this history in my mind that I approached my art.

These poor unsuspecting people were imprisoned through no fault of their own into a hell hole of despair, laid together in the spoon position in this their Middle Passage — the second leg of their journey across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe and Africa.

The Middle Passage has its equivalent to me of what is perceived as my Midlife Crisis. It was at age 40 that I began my art teaching career, Little did I know that it would in turn be a journey of breaking free from a life of left brain isolation, perceived expectations of a suburban housewife, and gradually understanding that I had something to say with my art. This in turn enabled me to become stronger, to question my preconceived “station” in life and standup for myself. This did not happen all at once. It took years.

Like the slaves, I realized that my “master” would never change, that the roses that came to me at my school were once again only a temporary fix—a device to “hoover” me in once again so the cycle could start all over again. And it did.

“40 years A Slave” was also my story.

In my art, I incorporated several techniques of African art. The calabashes of “Strength”, “Defiance” and “Home” are made from lino blocks and originate in the Adinkra symbols of Ghana.

Metal work is an important component of African art as well. The baby spoon symbolizes the importance of raising your children well so that kindness is a part of their character. It also eludes to the “spoon” position that the Africans were forced into as they were stored on the slave ships. The gold patterns I took directly from the illustrations of Mud Cloth from our reference book.

The portrait is of myself completed in 1999 at Nimrod. I remember thinking of Vincent when I painted it using oil sticks. The subsequent tear is new. The cowry shells are an important part of African culture, used as money and a position of status in their clothing accoutrement.

The black chain and the four ships represent the journey of no return into the unknown. They are relevant to me as I made that journey as a child from England to America. The ships themselves are the pieces used in a game I played that traversed the island of Great Britain.

Joining the two canvases was a challenge to me. My main concern was to show despair into joy. I have truly found that. My device was through color and obviously the circles for the double wedding band. I on purpose did not focus so much on the wedding band as the strength of the composition but more as a background for life events.

Not being a fiber artist, I found the use of fabric to be challenging. Using the circle shapes as transitions from one canvas to another I whip stitched each and left them as pockets into which I inserted scrolls with words written on them. They are removable.

One of my all time favorite spirituals is “Swing Low Sweet Chariot”. I understand that Harriet Tubman used it to warn her charges. The eyes are mine. There are many messages there.

Bookmarking my Faith represents my travels and solo journeys I have taken across the globe since I set myself free. The lace is from Burano, Italy.

The tree with the cardinal and subsequent verse down below is from a recent card I received from my missionary friend, Mary Beth. She and her husband are with Water.org and frequently in Africa digging wells for the villages.

Writing for me is a large part of my creative process and I write many times on my art. I tried to make it legible but also felt it was alright to be childlike.

Lastly, the heart in the center is one that I made when I became the new me. Deformed, Devalued and Demeaned. No more.

Flying Geese

Donna Gallucci

fused glass

A signal to follow the direction of the flying geese as they migrated north in the spring. Most slaves escaped during the spring; along the way the flying geese could be used as a guide to find water, food and places to rest.

Donna Gallucci

fused glass

A signal to follow the direction of the flying geese as they migrated north in the spring. Most slaves escaped during the spring; along the way the flying geese could be used as a guide to find water, food and places to rest.

Flying Geese

Revelle Hamilton

mixed media

Flying Geese pattern told the slaves to follow migrating geese north towards Canada and to freedom. This pattern was used as directions as well as the best season for slaves to escape. Geese fly north in spring and summer. Geese also stop at waterways along their journey to rest and eat.

I Interpreted Flying Geese in paper, painting the red and blue "fabrics" in African motifs. The green triangles represent maps of the corn fields and may have aided slaves who were unfamiliar with the layout of a specific plantation to find their way

Revelle Hamilton

mixed media

Flying Geese pattern told the slaves to follow migrating geese north towards Canada and to freedom. This pattern was used as directions as well as the best season for slaves to escape. Geese fly north in spring and summer. Geese also stop at waterways along their journey to rest and eat.

I Interpreted Flying Geese in paper, painting the red and blue "fabrics" in African motifs. The green triangles represent maps of the corn fields and may have aided slaves who were unfamiliar with the layout of a specific plantation to find their way

Flying Geese

Allyson Turner

fabric

Allyson Turner

fabric

Drunkards Path

Dotti Stone

mosaic

Drunkard’s Path is a very simple design composed of changing orientations of 16 squares composed of two shapes: a quarter circle, and the surround. Simple shapes at a glance, but a somewhat advanced pattern due to the curved shapes. In this mosaic interpretation of Drunkard’s Path for this Underground Railroad Project, varying the size of the components of the design adds to the complexity of walking a zig zag route to elude pursuers. Dotti Stone

Were Quilts Used as Underground Railroad Maps? Legend has it that runaway slaves sought clues in the patterns of handmade quilts.

By Diane Cole, Contributor June 24, 2007, at 12:45 p.m. U S News & World Report

Fact, fiction, folklore, or a bit of all three: Did runaway slaves seek clues in the patterns of handmade quilts, strategically placed by members of the Underground Railroad?

This ongoing debate surfaced as front-page news earlier this year when a New York City Central Park memorial to Frederick Douglass was slated to include two plaques referring to this code. Historians cried foul—loudly. There is no evidence for such a code, says Giles Wright, director of the Afro-American History Program at the New Jersey Historical Commission. "I know of no historian who supports this idea, and it's extremely rare to get that kind of consensus."

Mention of the quilt symbols in that plaque's text will now be omitted. But the quilt key legend itself remains very much above ground. Since 1999, when Jacqueline L. Tobin and Raymond G. Dobard published their bestseller, Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad, the secret-code story has woven its way into American folklore.

But historians note that the sole source for that story was one woman—Ozella McDaniel Williams, a retired educator and quilt maker in Charleston, S.C., who recounted for Tobin a family tradition that had been passed down to her through the generations. Embedded in 12 quilt patterns, she said, were directions to aid fugitive slaves on their journey to freedom. Depending on the pattern, a seemingly innocent quilt left on a porch or fence or hung in a window could signal to slaves on the plantation to get ready to escape (Monkey Wrench pattern), go north (North Star pattern), or zigzag to throw off pursuers (the Drunkard's Path pattern).

Although Williams died shortly before the book was published, her 73-year-old niece, Serena Wilson of Columbus, Ohio, says she also learned about the hidden maps from Williams's mother. "The quilt code was kept secret because it was dangerous to talk about escaping," Wilson says.

Misinterpret. But there is no reference for the code beyond that family, contends Fergus M. Bordewich, author of Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America. "There's no mention anywhere by anyone, African-American or white, of any quilt being used at any time." Nor do coded quilts from the period survive. Quilt historian Barbara Brackman notes that there is abundant evidence that slaves did sew quilts and that abolitionists made quilts to raise money for their antislavery activities. But some of the patterns that are said to be part of the Underground Railroad code did not exist until well after the Civil War, Brackman says.

Tobin believes her book has been misinterpreted. Numerous details ascribed to the story—like hanging quilts along the way to indicate safe houses—"simply aren't in the book," she says. Moreover, "We make it clear that this was Ozella's story only," she says, and that such codes "could have" been used in this way and only on one particular plantation. "We're not talking about hundreds or thousands of folks using this code," says Tobin. "The story has grown in ways that we had not intended."

Drunkard's Path

Another name for the Drunkard’s Path pattern is the Solomon’s Puzzle pattern. The origin of this pattern can be traced back to Ancient Egypt.

American oral tradition states that this quilt design was used along the Underground Railroad to help slaves find their way to freedom; however, the use of quilts is widely debated among quilt historians. The drunkard’s path quilt is characterized by its zig zag pattern made of curved fabric pieces that resemble the meandering path a drunk might take on his way home; symbolic to the Underground Railroad movement, it was meant to warn people to take a zigzag pattern to confuse those who might be following them.

Prohibited from voting, the Drunkard's Path was a popular way for a woman to express her opinion on alcohol and its use. It appears that more quilts were made for this cause than for any other. Other stories suggest that the zig zag pattern first originated with the Women’s Temperance Movement in the early 20th Century. This last movement is considered the third wave of temperance and began in the 1890s. This period saw the rise of the Anti-Saloon League, first organized in 1893.

Dotti Stone

mosaic

Drunkard’s Path is a very simple design composed of changing orientations of 16 squares composed of two shapes: a quarter circle, and the surround. Simple shapes at a glance, but a somewhat advanced pattern due to the curved shapes. In this mosaic interpretation of Drunkard’s Path for this Underground Railroad Project, varying the size of the components of the design adds to the complexity of walking a zig zag route to elude pursuers. Dotti Stone

Were Quilts Used as Underground Railroad Maps? Legend has it that runaway slaves sought clues in the patterns of handmade quilts.

By Diane Cole, Contributor June 24, 2007, at 12:45 p.m. U S News & World Report

Fact, fiction, folklore, or a bit of all three: Did runaway slaves seek clues in the patterns of handmade quilts, strategically placed by members of the Underground Railroad?

This ongoing debate surfaced as front-page news earlier this year when a New York City Central Park memorial to Frederick Douglass was slated to include two plaques referring to this code. Historians cried foul—loudly. There is no evidence for such a code, says Giles Wright, director of the Afro-American History Program at the New Jersey Historical Commission. "I know of no historian who supports this idea, and it's extremely rare to get that kind of consensus."

Mention of the quilt symbols in that plaque's text will now be omitted. But the quilt key legend itself remains very much above ground. Since 1999, when Jacqueline L. Tobin and Raymond G. Dobard published their bestseller, Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad, the secret-code story has woven its way into American folklore.

But historians note that the sole source for that story was one woman—Ozella McDaniel Williams, a retired educator and quilt maker in Charleston, S.C., who recounted for Tobin a family tradition that had been passed down to her through the generations. Embedded in 12 quilt patterns, she said, were directions to aid fugitive slaves on their journey to freedom. Depending on the pattern, a seemingly innocent quilt left on a porch or fence or hung in a window could signal to slaves on the plantation to get ready to escape (Monkey Wrench pattern), go north (North Star pattern), or zigzag to throw off pursuers (the Drunkard's Path pattern).

Although Williams died shortly before the book was published, her 73-year-old niece, Serena Wilson of Columbus, Ohio, says she also learned about the hidden maps from Williams's mother. "The quilt code was kept secret because it was dangerous to talk about escaping," Wilson says.

Misinterpret. But there is no reference for the code beyond that family, contends Fergus M. Bordewich, author of Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America. "There's no mention anywhere by anyone, African-American or white, of any quilt being used at any time." Nor do coded quilts from the period survive. Quilt historian Barbara Brackman notes that there is abundant evidence that slaves did sew quilts and that abolitionists made quilts to raise money for their antislavery activities. But some of the patterns that are said to be part of the Underground Railroad code did not exist until well after the Civil War, Brackman says.

Tobin believes her book has been misinterpreted. Numerous details ascribed to the story—like hanging quilts along the way to indicate safe houses—"simply aren't in the book," she says. Moreover, "We make it clear that this was Ozella's story only," she says, and that such codes "could have" been used in this way and only on one particular plantation. "We're not talking about hundreds or thousands of folks using this code," says Tobin. "The story has grown in ways that we had not intended."

Drunkard's Path

Another name for the Drunkard’s Path pattern is the Solomon’s Puzzle pattern. The origin of this pattern can be traced back to Ancient Egypt.

American oral tradition states that this quilt design was used along the Underground Railroad to help slaves find their way to freedom; however, the use of quilts is widely debated among quilt historians. The drunkard’s path quilt is characterized by its zig zag pattern made of curved fabric pieces that resemble the meandering path a drunk might take on his way home; symbolic to the Underground Railroad movement, it was meant to warn people to take a zigzag pattern to confuse those who might be following them.

Prohibited from voting, the Drunkard's Path was a popular way for a woman to express her opinion on alcohol and its use. It appears that more quilts were made for this cause than for any other. Other stories suggest that the zig zag pattern first originated with the Women’s Temperance Movement in the early 20th Century. This last movement is considered the third wave of temperance and began in the 1890s. This period saw the rise of the Anti-Saloon League, first organized in 1893.

Follow the Drinking Gourd*

Mitchell Bond

pen and ink doodles

Times of struggle require new ways of seeing, new ways of understanding, new ways of living. Map makers combine color and pattern to set the course – follow, follow, follow. Singers and dancers dictate the movement – feet to the ground, eyes to the sky. Visioners – starry-eyed yet rooted – tell of the promises yet to come.

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is comin' just to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

When the sun comes back, and the first quail calls

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is waiting just to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is waiting to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

Well the river bank makes a mighty good road

Dead trees will show you the way

Left foot, peg foot, travelin' on

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is waiting to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

Well the river ends, between two hills

Follow the drinkin' gourd

There's another river on the other side

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is waiting to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

- traditional African American Spiritual

*The “drinking gourd” is a reference to the Big Dipper constellation which points to the North Star

Mitchell Bond

pen and ink doodles

Times of struggle require new ways of seeing, new ways of understanding, new ways of living. Map makers combine color and pattern to set the course – follow, follow, follow. Singers and dancers dictate the movement – feet to the ground, eyes to the sky. Visioners – starry-eyed yet rooted – tell of the promises yet to come.

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is comin' just to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

When the sun comes back, and the first quail calls

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is waiting just to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is waiting to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

Well the river bank makes a mighty good road

Dead trees will show you the way

Left foot, peg foot, travelin' on

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is waiting to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

Well the river ends, between two hills

Follow the drinkin' gourd

There's another river on the other side

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is waiting to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

- traditional African American Spiritual

*The “drinking gourd” is a reference to the Big Dipper constellation which points to the North Star

A Tribute to Harriet Tubman

Patty Malanga

fused glass

…I set the North Star in the heavens and I mean for you to be free…

Harriet Tubman was an American abolitionist and political activist. Born into slavery Tubman escaped and subsequently made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people, including family and friends, using the network of antislavery activists and safes houses known as the Underground Railroad.

Patty Malanga

fused glass

…I set the North Star in the heavens and I mean for you to be free…

Harriet Tubman was an American abolitionist and political activist. Born into slavery Tubman escaped and subsequently made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people, including family and friends, using the network of antislavery activists and safes houses known as the Underground Railroad.

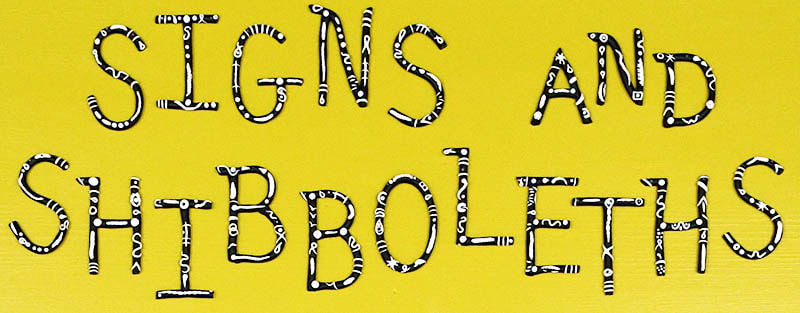

Quilt Journey Markers

Sharon Kessler

polymer clay

At the first meeting of artists for this project, everyone else had already chosen a quilt block they were inspired to create. I was hoping one of the blocks would just jump out at me as “the ONE”, but it didn’t happen. While listening to the artist who conceived this project explain her vision of the show, she mentioned the need to display a mnemonic that would form a path between the blocks. Immediately, I pictured some kind of hand sculpted letters that would tell their story and volunteered. A few days later as I rolled the black clay between my hands to form the body of the letters, images of African art kept running through my mind. With a pinch or two of white clay shaped into little embellishments, it was exciting to see the letters start taking on a sort of tribal appeal that I felt lent itself well to telling this amazing story.

Sharon Kessler

polymer clay

At the first meeting of artists for this project, everyone else had already chosen a quilt block they were inspired to create. I was hoping one of the blocks would just jump out at me as “the ONE”, but it didn’t happen. While listening to the artist who conceived this project explain her vision of the show, she mentioned the need to display a mnemonic that would form a path between the blocks. Immediately, I pictured some kind of hand sculpted letters that would tell their story and volunteered. A few days later as I rolled the black clay between my hands to form the body of the letters, images of African art kept running through my mind. With a pinch or two of white clay shaped into little embellishments, it was exciting to see the letters start taking on a sort of tribal appeal that I felt lent itself well to telling this amazing story.